You’re wrapped in blankets, it’s way past bedtime, torch and book in hand, you venture off to other worlds and wild adventures…

You’re in a calm spot in the playground during lunch, snack in hand and one of those awesome books from the book fair in the other…

You look up from a two-hour car journey, oblivious to the entire drive because you were so engrossed in your story…

Having that book in your hand may have been a significant part of your childhood (I know it was part of mine).

However, for almost one out of every five UK children, these experiences may sadly be alien and unheard of for them. Though, as we may find below, the truth could be a little more promising.

The headline behind the headline

In a study conducted by the National Literacy Trust, researchers found that 18.6% of UK children aged between five and eight do not have a single book that is theirs at home.

In a study conducted by the National Literacy Trust, researchers found that 18.6% of UK children aged between five and eight do not have a single book that is theirs at home.

It’s a fairly shocking statistic, and one that can be hard to imagine for book lovers. It’s also one that many commentators (such as this recent Guardian article) have been quick to jump on.

Personally, I find the focus on book ownership a bit odd. After all, you can own a whole library of books and never read any of them. In fact, there are considerably more concerning statistics to consider (which I’ll go into later in this post).

How do different families define ‘ownership’?

On the subject of ‘ownership’, I have a few concerns. Firstly, children self-reported their book ownership, and this leaves a lot of room for misunderstandings and misinterpretations.

It’s also worth remembering that these children may have hand-me-down books from older siblings or parents. The chance that this alone would prevent a child from describing such books as ‘theirs’ is minimal. However, it does speak to a potential bias to be found when assessing ‘ownership’ in some households.

I had access to many books as a child, only a handful of these were books I would have described as ‘mine’ at the time, and even then I would only think of myself as ‘owning’ books when I was a little older. The other books in the house were treated in a more utilitarian manner. Basically, most of the books in our house were ‘family books’.

Books as a shared family resource

Many families encourage an outlook like this regarding resources like books, toys, games, game systems, and more. A more utilitarian approach could come from a number of reasons, whether it’s a household where money is tight or simply a household that avoids conflict over leisure resources. In households where parents choose this more utilitarian approach, the children themselves may not feel that it’s appropriate to describe themselves as ‘owning’ certain toys, and perhaps books as well.

Many families encourage an outlook like this regarding resources like books, toys, games, game systems, and more. A more utilitarian approach could come from a number of reasons, whether it’s a household where money is tight or simply a household that avoids conflict over leisure resources. In households where parents choose this more utilitarian approach, the children themselves may not feel that it’s appropriate to describe themselves as ‘owning’ certain toys, and perhaps books as well.

A favourite teddy bear may belong to an individual child but maybe toy cars or lego blocks are sort of “everyone’s”. In circumstances such as this, books could theoretically be regarded in a similar fashion.

I’m not saying this is the situation in the case of every one of those ‘one in five’ but the potential is there for a five-year-old to regard themselves as a non-book-owner in a household where books are a family resource.

Libraries are amazing!

It’s also worth remembering that library use is heavily promoted by most primary schools at this stage in a child’s life (5-8 years old). They might not consider themselves to own any books, but they could still be reading regularly.

Half of the children surveyed said that they read daily, with twelve in every thirteen children saying that they read sometimes at home.

This made me pause; if twelve children out of thirteen still read occasionally at home, then where are they getting access to that reading material? As noted, maybe self-reported book ownership isn’t everything.

A More Concerning Statistic

However, let’s circle back to a more real and still troubling statistic.

However, let’s circle back to a more real and still troubling statistic.

It’s true that, despite the apparent lack of access implied by not owning their own books, twelve out of every thirteen children reported that they read at home. If these results are to be believed, then twelve out of thirteen children aged 5 to 8 are reading sometimes.

Something encouraging seems to be happening here. I’d like to think that access to library books and other borrowed reading material plays a role (though I don’t have any figures to back that up).

However, we still have a child missing out on the benefit of reading. It may not be the one in five kids who report not owning a book, but there is a child in every thirteen who reports never reading. I feel this is the child we should be concentrating on.

Who isn’t reading?

The related statistic that I feel we should return to is this idea that one in thirteen of the children surveyed supposedly ‘never read’.

However, even here, I can’t help but wonder if this ‘scary number’ might be able to be softened a little.

First, let’s think about their sample age group; the children in this study were between the ages of five and eight. Whilst many five-year-olds can read surprisingly well, I do have doubts that a significant number of them would be doing so with enough confidence to say that they read for pleasure themselves at home.

Let’s also remember that reading confidence may come on much more slowly for some children. Factors such as learning impairments, as well as issues regarding concentration, will inevitably make it harder for a child to self-describe as a ‘reader’.

Just looking at dyslexia, the NHS website lists the estimated UK incidence of dyslexia as one in ten. However, Dyslexia comes in varying levels of severity, so I wouldn’t suggest that this will be the only influence on readership in children between five and eight years old.

I know several people with dyslexia who happen to be more avid readers than I am (and were so as children too), so I won’t simply jump to the conclusion that a child being dyslexic will instantly mark them as a ‘non-reader’.

All in all, I’m finding it hard to come to any concrete conclusion from the National Literacy Trust’s findings. So let’s return to the matter that many news outlets have focused on; book ownership.

Why get so hung up on book ownership?

As an author, I obviously see a more pragmatic benefit from people buying my books for their children. Book ownership supports your favourite authors and helps ensure the publication of more books you like. Is this important for child literacy, though? No, not really.

As an author, I obviously see a more pragmatic benefit from people buying my books for their children. Book ownership supports your favourite authors and helps ensure the publication of more books you like. Is this important for child literacy, though? No, not really.

So, what is the argument for having a child perceive some books as ‘theirs’?

For some families, the purchase of a book may seem frivolous, an unnecessary expense when libraries are available. As a parent, I’m aware of how much it costs to provide your child with all the other things they need. If money gets tight, I imagine sacrificing book ownership seems like a small sacrifice in the face of other financial concerns.

I prioritise book ownership because I (and my wife) like to read. However, this isn’t enough on its own for anyone to criticise or question another parent who doesn’t prioritise book ownership.

My children typically get a few new books for their birthdays and more for Christmas. I also use Kindle Unlimited myself, meaning that they can access any Unlimited book they like using my account (and read it using our kindle, our household tablet, or on the app on their phones).

They both read fairly regularly, and I know that this provides considerable educational benefits (as I’ve noted in a previous blog post). However, they also both get books from the library. Between library use and the Kindle Unlimited lending library, often what they read wouldn’t count as ‘their’ books either.

This said, I know my children are in a privileged position when it comes to book ownership. Reading for pleasure and literacy proficiency aren’t just ‘nice to have’ perks; they have a profound and tangible effect on job prospects.

Keep reading for pleasure

Oxford Uni conducted a study on the correlation between reading for pleasure as a teen and management positions later in life. The results are fascinating, but, needless to say, it’s probably a good idea to encourage teenagers to read for pleasure as well.

Childhood reading can also influence your adult wage level (especially if you start off less well off). In a study for ‘The Institute for Fiscal Studies’ (Crawford and Cribb, 2015) their findings gave little correlation for other quality of life indicators. However, in terms of average wage, those who read as children had a much better rate of pay as adults.

Childhood reading can also influence your adult wage level (especially if you start off less well off). In a study for ‘The Institute for Fiscal Studies’ (Crawford and Cribb, 2015) their findings gave little correlation for other quality of life indicators. However, in terms of average wage, those who read as children had a much better rate of pay as adults.

In another study (2021), The National Literacy Trust pointed out a similar important correlation between book ownership and literacy:

“…children who reported that they had a book of their own were not only more engaged with reading but also six times more likely to read above the level expected for their age than children who didn’t own a book (22% vs. 3.6%)…” (‘Book Ownership in 2021‘ posted on the National Literacy Trust’s website 12 Nov 2021

There’s no question that book ownership is a good thing for children. My primary concern is whether news sources like the Guardian are focusing too strongly on ownership. As though simply owning a book is ‘enough’.

But why are so many children not reading at all?

Perhaps, but perhaps some children aren’t reading for other reasons. I’m most interested in what’s happening with the one in thirteen who report that they ‘never read’.

The statistics for non-readers are presented in the Guardian as though they’re a worrying new development. However, it would seem that 1 in 13 non-readers has been a UK constant for some time.

Is this lack of reading a ‘new development’?

The reported one in thirteen ‘non-readers’ (7.7%) is remarkably close to the same figures regarding ‘non-readers’ in a similar 1980s study on the same subject (here it was 7.3%). This study was conducted by the Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University College London.

The reported one in thirteen ‘non-readers’ (7.7%) is remarkably close to the same figures regarding ‘non-readers’ in a similar 1980s study on the same subject (here it was 7.3%). This study was conducted by the Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University College London.

For four decades (at least), one out of every thirteen British children has reported themselves as not reading for pleasure/recreationally.

Many factors may lead to their lack of recreational reading. A lack of book ownership may (of course) play some part in this, but I suspect that it isn’t the only reason that these children don’t read.

Whatever the cause may be, there’s little doubt that their lack of recreational reading will have a negative effect on both their personal and professional lives.

In a previous post, I looked in much more detail at the positive effects of recreational reading, so I won’t go into it too much here. Needless to say, reading recreationally is proven to be good for an individual on multiple levels.

The positive responses to a tricky problem

Obviously, any country would hope to promote a behaviour that has a positive effect on its citizens’ future. Seeing the number of non-recreational readers go up over the course of forty years is not exactly ideal (if only by a fraction of a percent). It is, however, promising to hear the measures described at the end of the Guardian article.

Private companies such as McDonald’s have made a concerted effort to get more books into the hands of children. On top of this, we have phenomenal events like World Book Day, which also strive for the same outcome.

In fact, World Book Day (also run by the National Literacy Trust) goes a step further, by hosting and promoting events and activities which help to normalise reading for children who may not otherwise recognise it as a ‘normal’ behaviour.

1 in 13 children not reading in 2022 is as troublesome now as it was in 1980. We should be doing what we can to lower this number. Reading is a phenomenal activity, whether viewed as leisure, an escape, or as a learning tool.

However, this statistic has only shifted by a minimal amount over the course of forty years so I’m also wary of treating it like a new development.

I suppose the moral of the story is that we should read more to our children. We should also buy books as gifts for any children we know (when finances allow), and (crucially, perhaps) we should try to normalise reading for pleasure. Children mimic what they see adults do, after all; if we adults read more, then it seems more like the ‘done thing’.

Normalising a healthy habit

The 1980s study also checked in with the children when they reached 16. At this point they asked about ‘reading culture’ at home. Only 43.6% reported that their dads read books, and 57.6% reported their mums reading books. Maybe if more of us allowed our children to see us reading (and enjoying) books, they might be more inclined to do it themselves.

The 1980s study also checked in with the children when they reached 16. At this point they asked about ‘reading culture’ at home. Only 43.6% reported that their dads read books, and 57.6% reported their mums reading books. Maybe if more of us allowed our children to see us reading (and enjoying) books, they might be more inclined to do it themselves.

The forty-year span of the one in thirteen non-readers may seem fairly inescapable. From the data we see, it would be easy to assume as much. However, I wouldn’t want to suggest that we go so far as to throw the baby out with the bath water.

Statistics such as these focus our attention on what matters to us as a culture. Do we want to promote literacy? Do we, as a culture, recognise its benefit?

Do we feel like we could (and should) encourage those final one in thirteen children to read?

If we answer yes to these (and it’s hard to find anyone who wouldn’t). If the end result of studies like the one conducted by the National Literacy Trust is more effort to get children reading. Then the study has done its job. Big headlines aside, the studies and stories themselves are there to remind us that, as a culture, we all want more children to feel the benefits of reading.

Starting small

If this post makes you feel inclined to buy a book for a young person you know, I would thoroughly recommend purchasing from a local bookshop. Your local bookshop will be able to advise you on great stories and appropriate reading levels, with marked expertise and you will also help support your local economy.

The range of children’s books available now is a vast, incredible cavalcade when compared to my childhood bookshelves. There are so many options that a child of any age and any interest might like. Your local bookshop will be able to guide you to the perfect book for the child you want to buy for.

What’s important to remember is this: even if all you do is share a love of reading, you’re already doing something fantastic. It allows you the chance to make a lasting impact on a young person’s wellbeing and learning journey.

Please don’t feel obligated

Alternatively, if you would like to buy one of my books, you could go to Fun Junction’s book section.

They deliver throughout the UK and have always been big supporters of my books, so I always like to return the favour where I can.

(Amazon is always there, and you can get my books on Kindle here, but I always personally prefer to support smaller, more independent online retailers).

Fun Junction also stocks a brilliant selection of toys, games, and puzzles for children and adults, so it’s well worth a visit to their website.

As always, thanks for reading, all the best, John

If you don’t have a kindle it’s no problem. So long as you have something that can run the kindle reader app (click on the link for a list of devices and how to use the app on them) then you can get hold of any book in their library.

If you don’t have a kindle it’s no problem. So long as you have something that can run the kindle reader app (click on the link for a list of devices and how to use the app on them) then you can get hold of any book in their library. ALL of the Harry Potter books: I don’t really need to describe these do I? World-famous fantasy books about a boy wizard and his adventures at a secret wizarding school.

ALL of the Harry Potter books: I don’t really need to describe these do I? World-famous fantasy books about a boy wizard and his adventures at a secret wizarding school. Skulduggery Pleasant (by Derek Landy): These books are phenomenal. A bit grittier and more violent that Harry Potter (Landy is a black belt and a screenwriter so his action scenes are superb, yet intense). NOT for younger readers. As far as I can see you can read the whole series FREE on Kindle Unlimited.

Skulduggery Pleasant (by Derek Landy): These books are phenomenal. A bit grittier and more violent that Harry Potter (Landy is a black belt and a screenwriter so his action scenes are superb, yet intense). NOT for younger readers. As far as I can see you can read the whole series FREE on Kindle Unlimited. The Lord of the Rings series by J R R Tolkien: An absolute classic and (probably) the core of most modern fantasy stories. An absolutely epic adventure. A famous Sunday Times quote is often cited about Lord of the Rings “‘The English-speaking world is divided into those who have read The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit and those who are going to read them.”

The Lord of the Rings series by J R R Tolkien: An absolute classic and (probably) the core of most modern fantasy stories. An absolutely epic adventure. A famous Sunday Times quote is often cited about Lord of the Rings “‘The English-speaking world is divided into those who have read The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit and those who are going to read them.” The Hobbit: OK, this is almost the same but it’s worth stating that there are a heap of digital editions of The Hobbit by J R R Tolkien but this is the only one I can see that is free on Kindle Unlimited. A total fantasy classic and suitable for a (slightly) younger audience than the Lord of the Rings books.

The Hobbit: OK, this is almost the same but it’s worth stating that there are a heap of digital editions of The Hobbit by J R R Tolkien but this is the only one I can see that is free on Kindle Unlimited. A total fantasy classic and suitable for a (slightly) younger audience than the Lord of the Rings books. The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling: A very different story than the one put together by Disney but very much worth a look. It includes lessons on life and has a general fable-like quality that you don’t often see in modern fiction anymore. Another great book you can read for free on Kindle Unlimited.

The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling: A very different story than the one put together by Disney but very much worth a look. It includes lessons on life and has a general fable-like quality that you don’t often see in modern fiction anymore. Another great book you can read for free on Kindle Unlimited. Jane Austen’s Complete novels, all in one book: These aren’t really for kids but they are some of my favourite books of all time. Austen is an absolute genius when it comes to dry wit and establishing character. Reading her works is an utter masterclass in writing characters and dialogue. I’m so happy to see her novels in one digital volume to read for free on Kindle Unlimited.

Jane Austen’s Complete novels, all in one book: These aren’t really for kids but they are some of my favourite books of all time. Austen is an absolute genius when it comes to dry wit and establishing character. Reading her works is an utter masterclass in writing characters and dialogue. I’m so happy to see her novels in one digital volume to read for free on Kindle Unlimited.

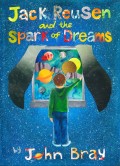

‘Jack Reusen and The Fey Flame‘ introduces you to the land of Fey, as creatures (and other things) make their way through to the ‘matter-world’ (basically our world). Jack and his family have to discover a way of closing a collection of ‘breaches’ between the two worlds to make their world safe again.

‘Jack Reusen and The Fey Flame‘ introduces you to the land of Fey, as creatures (and other things) make their way through to the ‘matter-world’ (basically our world). Jack and his family have to discover a way of closing a collection of ‘breaches’ between the two worlds to make their world safe again. ‘Jack Reusen and the Spark of Dreams‘ is a slightly different kind of adventure. People are losing their ability to dream. Every night more and more people lose the certain something that makes human beings so good at solving problems and creating things; the spark of dreams. Jack discovers that he could be the key to understanding what’s causing this change, and he may even be the only person who can solve it and bring back the dreams and imaginations of hundreds of people.

‘Jack Reusen and the Spark of Dreams‘ is a slightly different kind of adventure. People are losing their ability to dream. Every night more and more people lose the certain something that makes human beings so good at solving problems and creating things; the spark of dreams. Jack discovers that he could be the key to understanding what’s causing this change, and he may even be the only person who can solve it and bring back the dreams and imaginations of hundreds of people.

In a

In a  Many families encourage an outlook like this regarding resources like books, toys, games, game systems, and more. A more utilitarian approach could come from a number of reasons, whether it’s a household where money is tight or simply a household that avoids conflict over leisure resources. In households where parents choose this more utilitarian approach, the children themselves may not feel that it’s appropriate to describe themselves as ‘owning’ certain toys, and perhaps books as well.

Many families encourage an outlook like this regarding resources like books, toys, games, game systems, and more. A more utilitarian approach could come from a number of reasons, whether it’s a household where money is tight or simply a household that avoids conflict over leisure resources. In households where parents choose this more utilitarian approach, the children themselves may not feel that it’s appropriate to describe themselves as ‘owning’ certain toys, and perhaps books as well. However, let’s circle back to a more real and still troubling statistic.

However, let’s circle back to a more real and still troubling statistic. As an author, I obviously see a more pragmatic benefit from people buying my books for their children. Book ownership supports your favourite authors and helps ensure the publication of more books you like. Is this important for child literacy, though? No, not really.

As an author, I obviously see a more pragmatic benefit from people buying my books for their children. Book ownership supports your favourite authors and helps ensure the publication of more books you like. Is this important for child literacy, though? No, not really. Childhood reading can also influence your adult wage level (especially if you start off less well off). In a study for ‘The Institute for Fiscal Studies’ (

Childhood reading can also influence your adult wage level (especially if you start off less well off). In a study for ‘The Institute for Fiscal Studies’ ( The reported one in thirteen ‘non-readers’ (7.7%) is remarkably close to the same figures regarding ‘non-readers’ in a

The reported one in thirteen ‘non-readers’ (7.7%) is remarkably close to the same figures regarding ‘non-readers’ in a  The 1980s study also checked in with the children when they reached 16. At this point they asked about ‘reading culture’ at home. Only 43.6% reported that their dads read books, and 57.6% reported their mums reading books. Maybe if more of us allowed our children to see us reading (and enjoying) books, they might be more inclined to do it themselves.

The 1980s study also checked in with the children when they reached 16. At this point they asked about ‘reading culture’ at home. Only 43.6% reported that their dads read books, and 57.6% reported their mums reading books. Maybe if more of us allowed our children to see us reading (and enjoying) books, they might be more inclined to do it themselves.